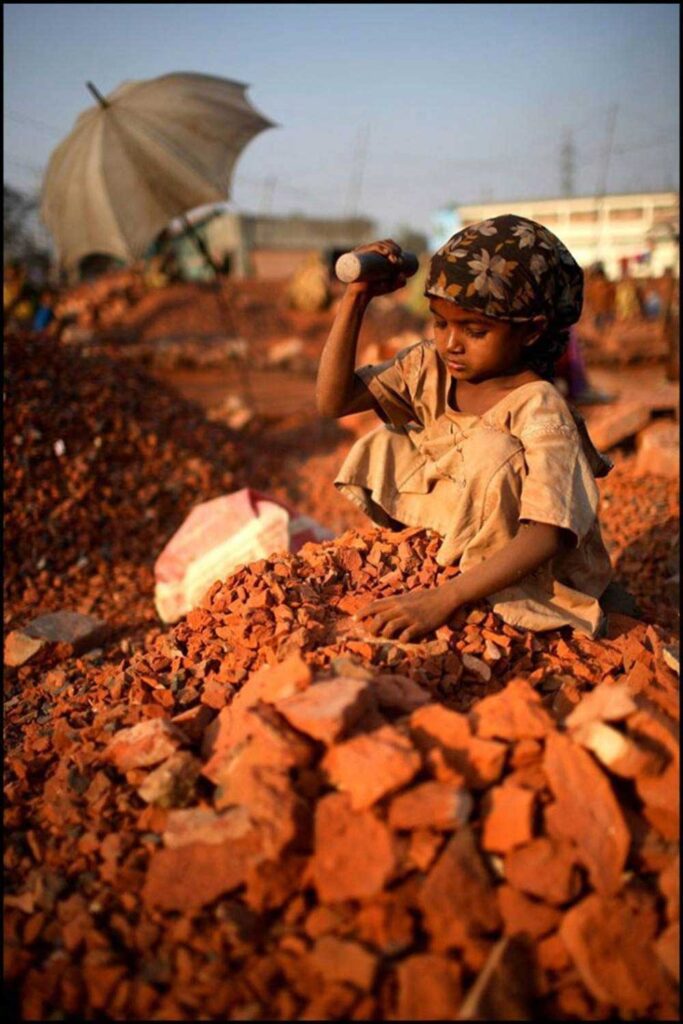

Child Labour

A chocolate bar often owes its existence to punishing hours of child labour. In Côte d’Ivoire and West Africa, the leading producers of cocoa, as many as 12,000 children are exploited for cocoa farming. Most of them don’t even go to school let alone know the taste of chocolate. All of us should know where the products we buy come from and how are they made. None of us want to do harm or to take advantage of impoverished adults and children.

Full-time labour is a physical, mental, and social danger to these children. They operate hazardous machinery, mix and apply chemicals to cocoa trees, harvest ripe cocoa pods with knives, and carry heavy bean sacks for processing. Long days mean missing school or dropping out altogether, extending the cycle of poverty and exploitation.

While organizations around the world implement projects for child protection and education, many children continue to be enslaved and trafficked to produce cocoa, clothing or rugs, with companies and governments more interested in money than improving conditions for child and adult labourers. It is a shame. It is a crime! Please don’t buy these products of exploitation.

The 2020 Global Estimates from UN’s International Labour Office showed that 160 million children – 63 million girls and 97 million boys – were in child labour globally at the beginning of 2020, accounting for almost 10% of all children worldwide. Almost half of those in child labour, 79 million, were in hazardous work that directly endangers their health, safety and mental development. The COVID-19 crisis likely drove millions more children into child labour.

Why should we care?

- Millions of children work in unacceptable conditions that are dangerous and tragic.

- Millions of child labourers are exploited and abused.

- Child labourers in developing countries often don’t get paid for their work or are paid much less than adult workers and are hardly able to contribute financially to their families.

- Child labourers are not able to receive school education.

- The estimated cost for the elimination of child labour is US$760 billion over a 20-year period.

To learn more about child labour, read UN’s Child Labour Global Estimates 2020 [ PDF ]

Fast facts

- 2021 is the International Year for the Elimination of Child Labour.

- Almost one in ten of all children worldwide are in child labour, and 1 out 20 children work in hazardous child labour (UN 2021). Those children often endure beatings, humiliation and sexual violence by their employers.

- Africa ranks highest among regions both in the percentage of children in child labour (one-fifth) and the absolute number of 72 million children in child labour.

- Asia and the Pacific ranks second highest in both percentage (7%) and the absolute number of 62 million.

- 70% of children in child labour work in agriculture, mainly in subsistence and commercial farming and herding livestock.

- UN estimates that 8.9 million more children will be in child labour by the end of 2022 because of rising poverty caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

- In 2020, almost half of the human trafficking victims in low-income countries were children who are mainly trafficked for forced labour.

- Around 1.2 million children were trafficked each year into exploitative work in agriculture, mining, factories, armed conflict or commercial sex trade (UN, 2002).

- In 2018, about one third of human trafficking victims were children – 15% for boys, and 19% for girls. Some children are forced to work up to 18 hours a day.

- Children are also trafficked in high-income countries in Europe or North America for forced labour and sexual exploitation.